Historical Background

Balochistan (highlighted in the map) is Pakistan’s largest province by area but remains sparsely populated and underdeveloped. Its accession to Pakistan in March 1948 was controversial: the Khan of Kalat’s agreement and his brother’s armed revolt against it “planted the first seed of Baloch insurgency”. Since then, Balochistan has seen at least five major uprisings (1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1990s, and post-2000) driven by demands for autonomy and rights. Observers note that Pakistan’s founder Jinnah insisted on the Kalat treaty, but many Baloch still view the 1948 annexation as illegitimate. Today about 15 million people live in Balochistan only around 6% of Pakistan’s population despite its vast mineral wealth (coal, gas, copper, gold, etc.). Analysts emphasize that Balochistan “remains the country’s poorest region despite being rich in natural resources”. This deep sense of marginalization born of contested history and one-sided federal integration underpins much of the pro-BLA sentiment.

Resource Exploitation and Autonomy

Baloch grievances often center on economic exclusion. Though the province generates substantial revenues (mining, energy, and the new Gwadar port), most profits flow to Islamabad or foreign investors. Critics argue that projects like the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) have bypassed local needs. As one analysis noted, “economic demands from Baloch society clashed with perceived exploitation of Baloch resources by the central government in Islamabad and by China” under CPEC. For example, local activists complain that few Baloch jobs or contracts are created by big-energy or infrastructure projects, reinforcing the view that Islamabad prioritizes Punjab or Chinese firms over provincial development. In theory, the 18th Amendment (2010) granted provinces more autonomy, but Baloch leaders say implementation has been weak. Many young Baloch feel excluded from decision-making and resent seeing military-run companies extract coal or gas with little benefit returning to their communities.

These economic disparities are stark. Balochistan’s per-capita GDP (around $1,600) is far below the national average, and literacy and health indicators lag other provinces. Local politicians have often warned Islamabad that insisting on centrally dictated development is unsustainable. In 1973, for instance, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto dissolved an elected Baloch provincial government amid such tensions. Political scientists point out that each time Baloch assemblies pressed for a greater share of royalties and development funds, they met with resistance or were disbanded. In sum, the combination of resource extraction, environmental damage, and limited local control has convinced many Baloch that “all major development in Balochistan has come at the cost of exploitation of our resources”, as one critic put it.

Military Crackdowns and Enforced Disappearances

Pakistan’s security approach in Balochistan has further eroded trust. Repeated military operations over the decades from 1970s sieges to the Taliban-era surge in the 2000s have involved heavy-handed tactics. Scores of Baloch activists, students, and even politicians have been detained without charge or simply vanished. Human rights monitors report thousands of such cases: one study found over 10,000 enforced disappearances nationwide between 2011 and 2024, including about 2,752 in Balochistan. (Another tally counted 8,463 missing persons over a similar period.) These victims are often thought to have been picked up by intelligence or paramilitary units and never seen again. Families protest relentlessly for information, but they too are punished: peaceful sit-ins in Quetta and Gwadar have been met with baton charges, tear gas, or even live fire. The Haq Do (Right to Know) movement, for example, held rallies demanding answers for abducted loved ones and was brutally dispersed. Amnesty International and local NGOs have documented this cycle of abduction and silence. Such stories of wrongful detentions and the state’s failure to resolve them have become a rallying point that the BLA and other insurgents use to justify armed resistance.

Media Narratives and Censorship

The Pakistani state tightly controls information about Balochistan. Journalists and media outlets face pressure to avoid any criticism of the military or to underplay Baloch grievances. According to Human Rights Watch, the government routinely “controls media and curtails dissent,” with journalists harassed or detained for reporting on sensitive issues. In practice this means that disappearances, protests, and even local political demands receive scant coverage in mainstream newspapers or TV (unless framed as “terrorism”). At times cable networks or websites that carry independent Baloch reporting have been blocked on orders from security agencies. Civil society groups note that when Islamabad announces big plans (like new pipelines or drilling projects in Balochistan), independent scrutiny is minimal. Baloch activists often rely on social media or foreign broadcasters to get their story out but these too can be throttled or censored under broad anti-terror laws. The end result is that many ordinary Pakistanis simply never learn about Balochistan’s struggles, while those in Balochistan feel their perspective is invisible. This lack of public dialogue reinforces the narrative that only militants will speak truth to power.

Recent Events and Political Triggers

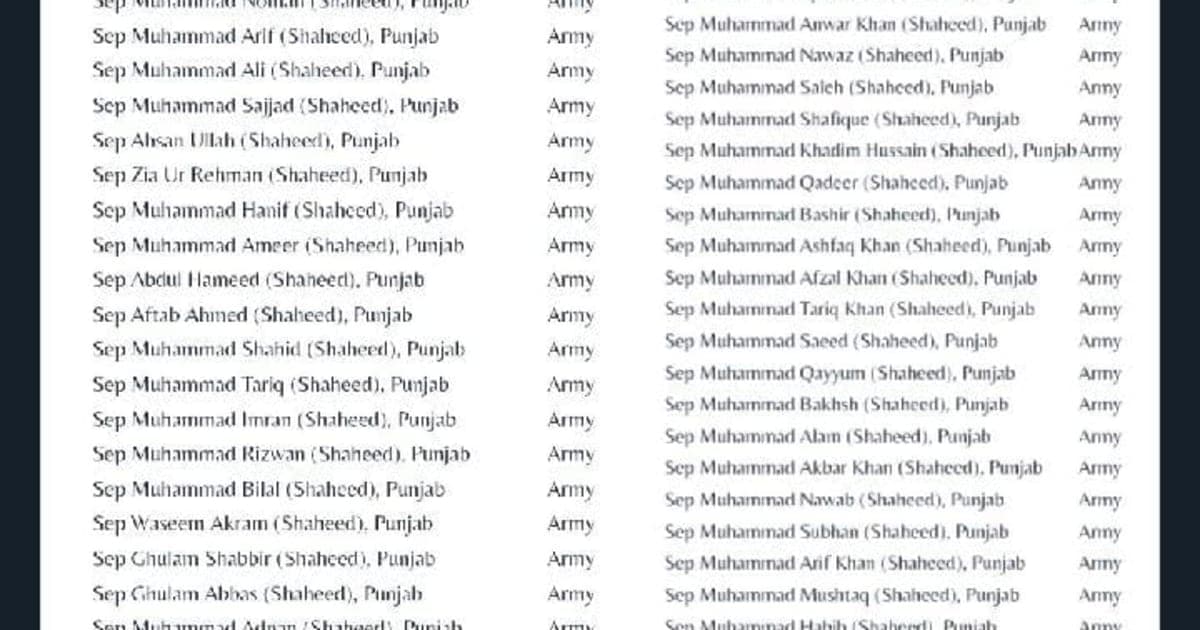

In the past year especially, several incidents have intensified Baloch resentment. The March 2025 Jaffar Express train hijacking by a BLA faction shocked Pakistan: gunmen took hundreds of passengers hostage in order to demand the release of political prisoners. The military’s rescue operation which killed the 33 BLA fighters created confusion over casualty figures. Official reports conflicted with insurgent claims about how many hostages were killed and how many militants were present, leading to rumors among locals about government obfuscation. Analysts warned that such opacity only “fueled…resentments among the local population that have resulted in the ongoing political turmoil in the province”. Other recent events include the killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti (a former tribal leader) in 2006 and the 2018 assassination of Akbar’s son Balach Marri; each of these galvanized support for separatists at the time. Protests over mine accidents, electrocutions, and other public grievances often ignored by the centre have likewise been met with force rather than remedies. All told, Baloch polling and anecdotal reports suggest that popular sympathy for the BLA’s goals (if not all its methods) has grown as routine political channels (elections, courts, media) appear blocked.

In Karachi and Quetta, many Baloch residents have also taken to the streets over social media campaigns and sit-ins. This image shows a protest (December 2020) after the mysterious death of Karima Baloch, a Karachi-based activist. Such demonstrations are increasingly common as people demand justice for the disappeared and an end to military impunity. The state’s response has generally been to brand these protestors as “anti-state elements,” restricting coverage of their demands.

Governance Failures and Ignored Grievances

In theory, Pakistan’s political system allows for provincial representation and resource-sharing. In practice, Balochistan’s civilian governments have frequently clashed with Islamabad. Critics point to chronic under-investment: despite large federal budgets allocated to the province, basic services like schools, hospitals, and clean water remain scarce in many districts. Even within the provincial assembly, MPs complain that approved development funds are re-routed by powerful outsiders (e.g. military-run contractors) or simply left unspent. Corruption is often cited; grand projects that were supposed to boost local economy (such as Special Economic Zones) rarely reach Baloch entrepreneurs.

This mismanagement feeds the sense that the state is indifferent or even hostile to ordinary Baloch. One insurgency expert observes that “the Baloch insurgency stems from long-standing grievances deeply rooted in the troubled post-partition era”. Every decade brings fresh disappointments: in 2004 it was broken promises of amnesty for insurgents; in 2012 the failure to hold perpetrators of killings accountable; in 2018 the grant of oil contracts that mostly favored out-of-province firms. When charismatic moderate leaders have tried to change things through politics for example, the Mengal family government in the 1970s and again in 1990s Islamabad effectively sidelined or arrested them. Meanwhile, the media and schools in the rest of Pakistan rarely mention these issues. As one columnist put it, “the Pakistani state has neglected [Balochistan’s] people while exploiting the province’s resources, triggering separatist movements and armed rebellions”.

Conclusion

After decades of broken promises and heavy-handed counterinsurgency, public sympathy for violent separatism has grown in Balochistan. Pakistani political actors from the military to feudal parties share much of the blame. State policies have historically prioritized security solutions over dialogue, and resource-sharing has been skewed against the province. Meanwhile, restrictions on free speech and reporting mean that few inside Pakistan even know the Baloch side of the story. Unless Islamabad fundamentally rebalances development and autonomy in Balochistan, analysts warn that even more youth will conclude that armed struggle is the only way to be heard. In short, the combination of historical mistrust, economic marginalization, rights abuses, and political neglect has fueled a cycle of anger, which insurgent groups like the BLA can exploit.