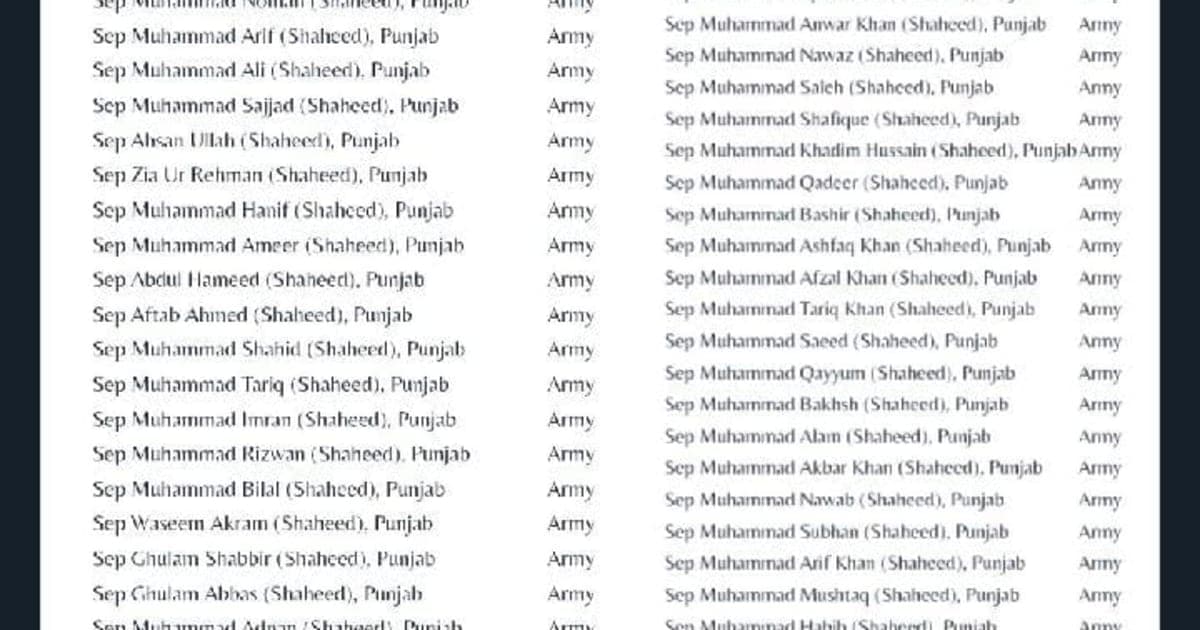

Women hold a complex status in Pakistan's political landscape. On one side, the nation is often praised for producing Benazir Bhutto, the first female leader of a Muslim-majority country, a landmark achievement that remains unmatched in several regions globally. Conversely, the involvement of women in mainstream politics is still limited in number and lacking in substance. According to the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) 2024 data women occupy 20.2 percent of seats in the National Assembly, whereas the worldwide average is 26.9 percent. Nearly all seats are obtained through reserved quotas. Only a small number of women have won general seats solely based on their own electoral efforts.

The gap between the constitutional commitments and the actual experiences of individuals has been extensively studied by researchers, electoral monitors, and advocates for women's rights. They highlight a network of structural, societal, and economic obstacles that persistently hinder women’s involvement in political arenas. However, in addition to these challenges, there are emerging possibilities such as increased representation in local government and digital campaigning that could transform the participation landscape if support is provided to them.

Barriers

Social and Cultural Norms

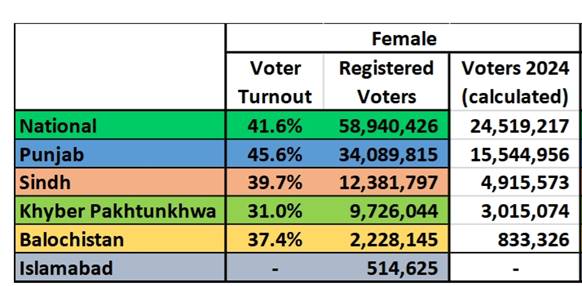

Social and cultural norms limit women's ability to participate in politics. In numerous rural regions, women are unable to attend campaign activities or vote without the consent of their male family members. In some areas, tribal councils or local customs explicitly prohibit women from exercising their right to vote. A survey conducted in 2024 by the Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) revealed that in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, more than 11 percent of women voters in specific districts were not allowed to caste their votes due to local "honor" restrictions.

(Source: Gallup Pakistan Election 2024 Dashboard (based on ECP data))

Financial Constraints

Contesting elections in Pakistan requires significant financial investment. Candidates often need to cover expenses for campaign events, promotional materials, and constituency outreach. However, with women constituting just 22.8 percent of Pakistan’s workforce (World Bank, 2024), many do not have access to their own financial means. The processes for party funding are unclear, and female candidates frequently rely on financial support from male family members.

Limited Political Independence

The Constitution allocates 60 seats in the National Assembly and 128 in provincial assemblies for women, yet most political parties rarely nominate women for general seats. Instead, women are often placed on “reserved lists,” which limits their political independence. Political parties largely view women as symbolic representatives or “vote banks” rather than as engaged contributors in decision-making processes.

Harassment and Violence Against Women

The emergence of digital campaigning has also made women more vulnerable to online harassment. A report from the Digital Rights Foundation in 2024 revealed that 65 percent of female politicians faced online abuse throughout the general election campaign, encompassing everything from character attacks to outright threats. In person, female candidates in Punjab and Sindh reported instances of intimidation from opponents, which further reduced the involvement.

Opportunities

Reserved Seats for Women

Reserved seats have created opportunities for women in legislative roles, enabling them to advocate for progressive initiatives. For example, during the 2018–2023 National Assembly term, female lawmakers proposed almost 40 percent of bills related to human rights, as reported by UN Women Pakistan.

Seats in Local Government

The devolution reforms introduced in 2002, which allocated 33 percent of local council seats for women, stand out as one of the most impactful measures for promoting political empowerment in Pakistan. During the local body elections in Punjab in 2024, over 36,000 women were elected to union councils, with many serving in such roles for the first time. While these positions may seem small, they offer women valuable political experience and credibility within their communities.

Civil Society and Media

Civil society organizations like Shirkat Gah and the Aurat Foundation have increased their efforts to promote voter registration and provide training for candidates. The Election Commission of Pakistan's 2024 initiative, “Women as Voters,” which received support from the International Growth Centre, has successfully registered over 2 million new female voters in preparation for the elections.

Additionally, social media has emerged as a means for young women politicians to overcome traditional barriers. Several well-known individuals have significant online followings, enabling them to connect directly with their supporters.

Global and Local Support

International organizations like UN Women and Oxfam have supported initiatives aimed at enhancing women's political influence. For example, Oxfam's 2024 project in Balochistan provided training to 500 women from rural areas on local governance, which boosted their involvement in village councils.

Future Directions: Aiming for Significant Participation

Experts argue that for women to have a significant role in politics in Pakistan, the country must transition from symbolic actions to true empowerment. They emphasize that reforming electoral laws to require parties to allocate a specific percentage of women on general seats would be a crucial initial step, similar to India’s recent initiative to ensure one-third representation for women in its legislative bodies. Additionally, addressing the voter gap is critical: the Election Commission has revealed that over nine million women, predominantly from the rural areas of Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, are still absent from voter rolls. Without targeted efforts for registration and easier access to identification cards, these women remain unheard. Another significant barrier is funding and security. Campaigning requires substantial funds, and in the absence of government supported financing or improved protection against harassment and violence, women often rely on their families or party benefactors. Some analysts have proposed establishing an Electoral Gender Equality Fund to level the playing field. However, only numbers and resources are insufficient; societal attitudes must also evolve. Educational institutions and the media can also contribute by presenting women in politics as normal citizens rather than extraordinary human beings. As an increasing number of voters become active online, digital participation has become essential. Equal and secure access to digital platforms, supported by strong measures against cyber-harassment, will determine whether the next wave of women leaders can express themselves or will be silenced once again.

Conclusion

Pakistan’s democratic progress cannot be completed without the equal and active involvement of women. Although quotas and efforts from civil society have opened pathways, systemic obstacles still hinder women's autonomous political influence. Yet, ongoing voter registration campaigns, local government reforms, and the digital empowerment of young female leaders indicate a gradual shift. As the nation moves forward, the key question is no longer if women should have a place in politics, but whether Pakistan is prepared to make changes to its institutions, social norms, and electoral procedures to provide women with the political opportunities they deserve.